The Roots We Spread

Abandonment has deep roots in my family history.

Premature deaths took the lives of several generations of my maternal grandparents and left young children without one or the other parent. The fierce sense of loss and sadness spread its roots like a cancer throughout my ancestry. Manifesting in misunderstood behaviors and denial of what those behaviors represented.

In 1895, at the age of five, my maternal great-grandfather (George) and his two brothers lost their mother. She was fifty-three. My great-great-grandfather remarried four years later. In 1900, their newly formed family set off on an adventure to the United States from southern Russia (Odesa, Ukraine region). Their destination, the central plains of North Dakota, to claim their free land along with many Germans from Russia during the turn of the century.

My great-grandfather George went on to marry at twenty-three, having three boys of his own (one of whom was my grandfather Joseph B. 1916). Tragedy struck when the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 took George at the age of twenty-eight, leaving his wife and three young sons behind. This was a heartbreaking repeat of the previous generation and what seems like a bizarre affliction in my lineage.

Six young boys' lives were forever changed, along with the roots they spread throughout their lives and future families.

Paths Taken

The childhood experiences of loss and abandonment can manifest in a variety of potentially brutal behaviors. And in the case of my ancestry, that proverbial can would be kicked down the road for subsequent generations to deal with.

Thus, generational trauma would dig in for the long haul.

Whenever I think about either of my grandfathers as young boys losing a parent, my heart aches. A strange but visceral connection that has been resurfacing since my mother passed away.

The paths my grandfather took were most likely a result of the tragic losses he, his father, and grandfather suffered so young. Longing to belong somewhere or with someone and never fully achieving it. My Grandfather Joe succumbed to the depths of alcoholism early and battled that demon for most of his life.

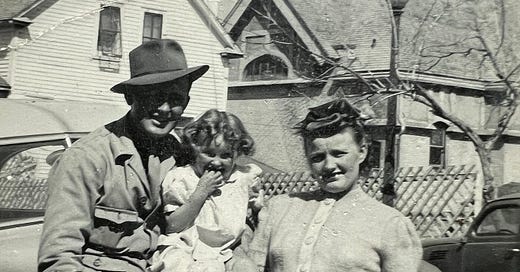

Grandpa first married in 1936 at the age of twenty and became a father at twenty-three. He divorced my grandmother when my mother was twelve. Their divorce certificate stated the reason was “cruelty.” I shuddered when that document first appeared in my research.

When humans hurt, those closest bear the brunt of the pain.

Mom was sent to live with her maternal grandparents because her mother was unable to care for her. The reasons are unclear, but there had been an accident. My imagination takes me to places I dare not go. Once again, the roots of abandonment resurface in different but equally damaging forms of loss.

My grandfather went on to marry and divorce twice more.

Re-opening A Door

Mom did not talk much about life with her parents. I never asked for fear of dredging up old wounds and horrible memories. But the past has a way of rising from the shadows, clamoring for attention with the possibility of clemency.

In the late 1970s, Mom received a call that Grandpa Joe was drinking heavily and needed to dry out somewhere outside the temptations of Great Falls, MT. There was more to the story, but I don’t remember being privy to the details. Grandpa Joe was in his 60s at that time. The demeanor of an alcoholic is averse to rational thinking or acting, especially at his age and with his sustained drinking habits. But my parents went to Montana to retrieve him anyway.

Mother was hopeful, but I imagine her being intuitively realistic. She set her expectations accordingly.

I was out of high school and meeting him for the second time since he first saw me as a baby in 1960. Grandpa seemed a skeptical and hardened man. Knowing more of his history, I have come to understand his disposition and the lack of trust he often put out into the universe. He grew up with only himself to rely on, and even that had been called into question.

For a brief time, Grandpa Joe allowed us a window into his sharable, PG-rated adventures. Mom always said he should have written a book of all his escapades. He was a complex man possessing both charm and sardonic wit, which probably contributed to his survival up to that point.

The idea of being around our family may have been too difficult for him because he did not stay long. Grandpa had put down roots in a particular enabling environment, and playing the family game without his vices would not have been possible. Besides, stability (at least where family was concerned) was not in his wheelhouse.

It’s difficult to steer a 60 plus year old man suffering from years of denied trauma and alcohol use toward a different trajectory when he perhaps had little reason to think life would or could be better. Those in addiction rarely feel they deserve anything better.

Harboring that kind of pain for so many years must have been a weight he believed only he could and should carry. Independent and tenacious to a fault, but I suspect he knew no other avenue. Behaviors and characteristics that run deep within our lineage.

I was sad to see Grandpa return to Montana because a part of me wanted him around a little longer. I was connected to him in ways that were unknown to me until later.

The Roots Continue to Weave

I regret not asking my mother more questions about her parents before she died. I can only hypothesize now. Issues of the past linger beneath the surface and do not dissipate with time. As a result, I believe a sadness continues to permeate within me and other family members along the line. A grief deeply affected by the tragic events that occurred at such vulnerable times in our ancestry. I feel those losses in my bones. Those roots run deep and wide.

I saw my grandfather several more times on my own and on his turf. His life experiences were forever evident on his face, but he always retained that twinkle in his eyes and a crooked smile ready to offer up some of his saucy wit. Feisty as ever (which is a loving term we used to describe my mother, too).

His advice to me was always to question the motives of others and to be vigilant. I took it as don’t trust just anyone or anything. Little did he know I had been practicing that strategy consciously and unconsciously for years. It was in my blood just as it was in his.

The roots of our past weave their way to the surface of our lives, attempting to reconcile the trauma.

The Last Time

His mannerisms were uncanny in their similarity to my mother’s. But their lives took very different turns. Mom’s early life of loss and instability was similar to her father’s. But once she married my Dad at 18, she created her own life, avoiding a repeat of the past. Her intention was to surround herself with the security and love of her own family. Mom often told me that is why she had children. She was an only child with parents unable to care for her, and she never wanted to feel that kind of loneliness.

I saw my grandfather once again when on my way through Montana in the late 1980s. It was an emotion-filled reunion that attached itself firmly to my heart and soul. I left with a pit in my stomach and an ache in my heart. Little did I realize it would be the last time I saw him alive.

He died alone in his apartment in 1990 at seventy-four years of age. Myocardial infarction as a result of years of arterial heart disease and COPD as a lifelong smoker. He had stopped drinking a while before his death, but the residuals of continued alcohol and tobacco use over the years took its toll on his body. His heart gave out and, in a sense, gave up.

I guess he no longer had the will to fight.

History repeated itself with my mother. Once my father died, she slowly, over the years, slipped into a state of melancholy. I suppose the internal sadness from past familial traumas eventually became too overwhelming. Her children could no longer fill the void of her loss (and losses).

She, too, no longer had the will to fight.

The Roots We Face

I am not one to live in the past or ruminate about my regrets. However, in researching my ancestry, I have gained a healthy respect for those who came before me and a more compassionate understanding of the behaviors exhibited throughout their lives. My grandfather did his best with the cards he was dealt. He was a proud man, steadfastly responsible only to himself. Seeking help did not seem conducive to that mindset.

Mom had her reasons for not giving up the ghosts of her past. It could have been to protect us, or talking about it would only make it more real. I do not know. But so much is out of our control, and those roots continue to spread and resurface without fail.

I cannot go back and re-enter the situation from a different angle. But I do imagine plucking my three year old grandfather from the depressing depths of 1918 and surrounding him with all the modern-day resources he would need to feel like he belonged. It could have changed the course of our history. But, of course, life does not work that way.

What I can do is learn from my history, understand the context, and move on with a renewed perspective of my own life and that of my family.